Up to date in March 2024; initially written prematurely of the August 2017 complete photo voltaic eclipse.

“The shades of night time which accompany an eclipse of the solar have at all times intrigued mankind and brought about him to pause, if just for a second, to ponder the thriller, the magic, the grandeur, and the extent of the universe of which he is part.”

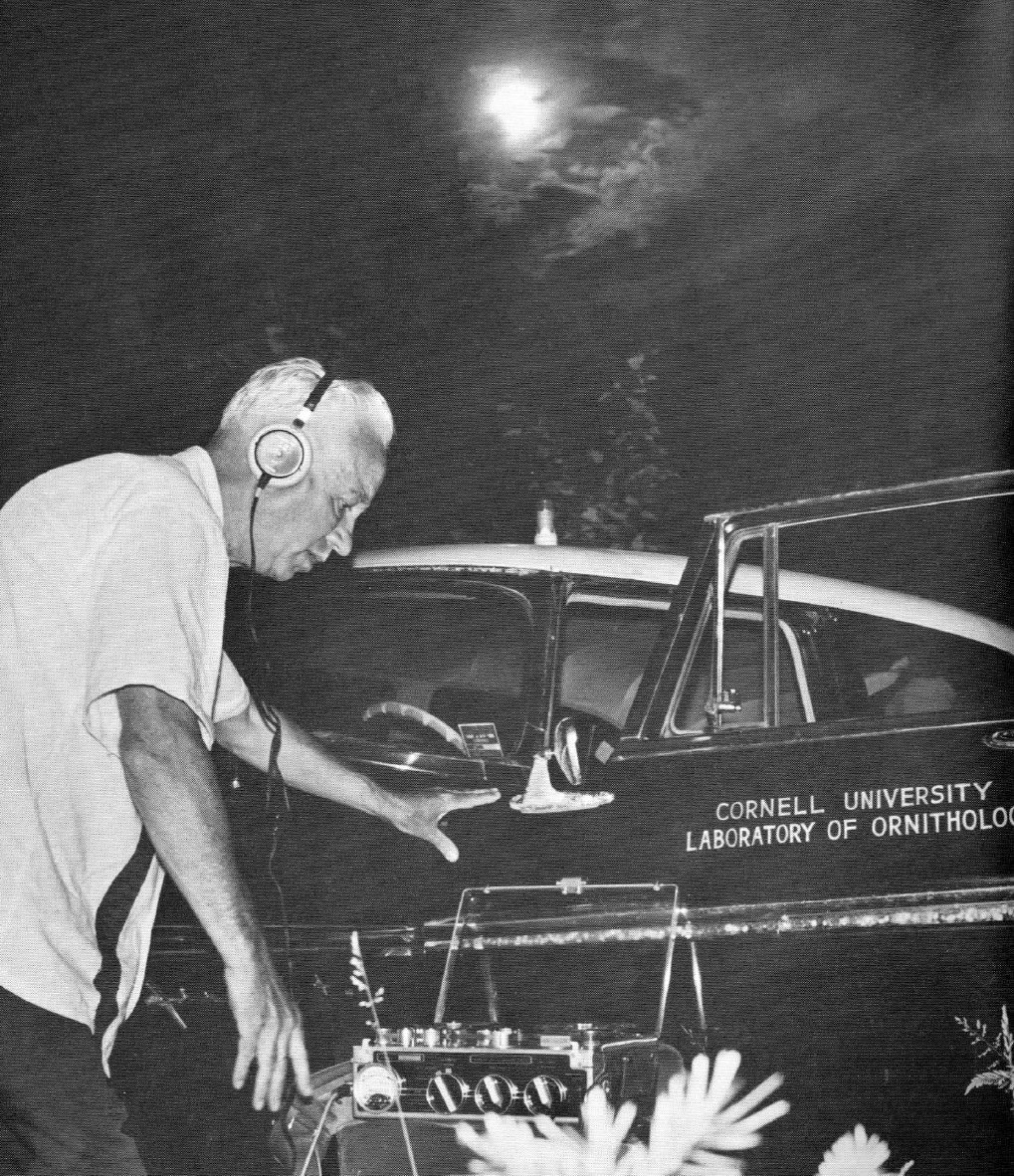

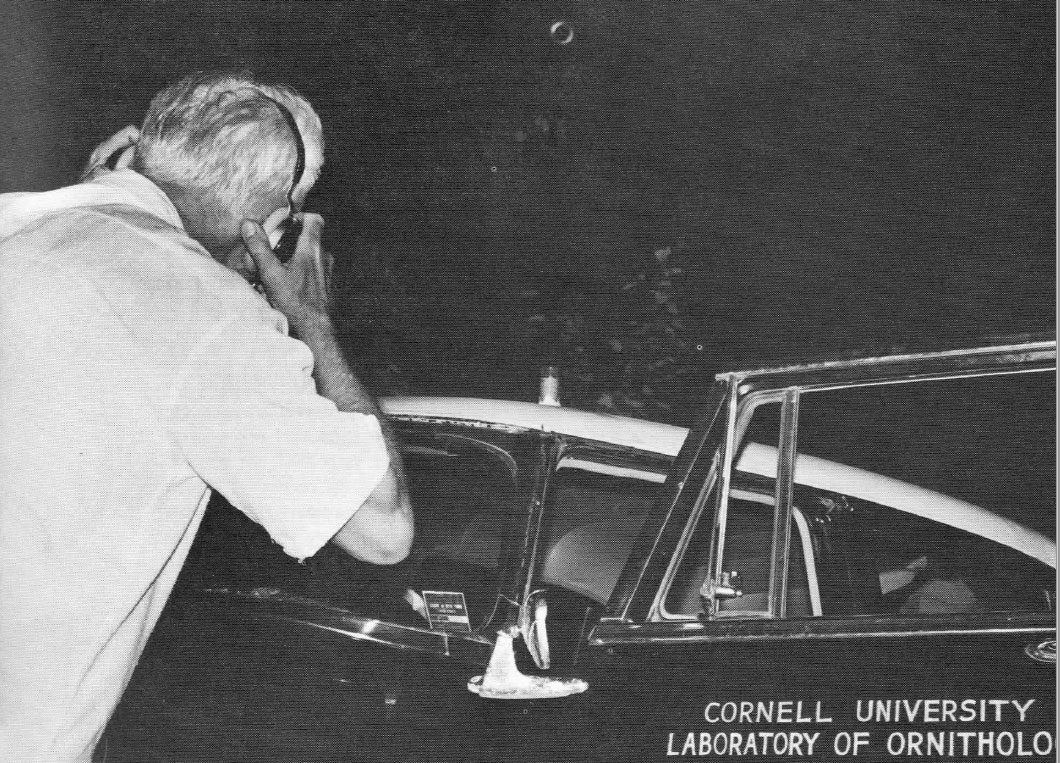

That’s the sort of sentiment that’s drawing 1000’s of individuals to the trail of the 2024 eclipse on April 8—however the phrases had been written in 1963, by Peter Paul Kellogg, a professor of ornithology and bioacoustics at Cornell. And it’s what drew him to Maine for that yr’s complete eclipse, at 5:30 p.m. on July 20. Many individuals had come to Maine to see the eclipse, however Kellogg was there to pay attention, and to document chicken songs.

As one of many pioneers of contemporary chicken sound recording, it was pure that Kellogg was occupied with capturing the vocal habits of as many birds as doable throughout this uncommon prevalence. It was the primary such complete eclipse seen within the U.S. since 1932, and the primary time wildlife recording know-how was actually as much as the problem of recording within the subject. But he did his greatest to maintain his expectations in test:

“The eclipse doesn’t affect most of the elements which have an effect on chicken music reminiscent of time of yr and the physiological situation of the chicken,” he wrote within the 1963 concern of The Dwelling Chicken. “It’s also possible that the sudden interruption of a longtime diurnal routine is extra complicated to some species or people than others. All these potentialities for variation in trigger and impact…are likely to preserve the worth of any statement a strictly native affair.”

However, because the occasion approached, Kellogg and colleague Calvin Hutchinson ready. An area hunter described a promising patch of woods close to Corinna, Maine. The pair drove their subject car, a Nineteen Fifties sedan with “Cornell College Laboratory of Ornithology” hand-lettered on the door panel, down an outdated logging highway and arrange in a forest clearing.

A late afternoon in midsummer may not appear optimum for capturing chicken music, however earlier than the eclipse started the pair famous basic Maine woods birds reminiscent of Olive-sided Flycatcher, Hermit Thrush, Swainson’s Thrush, Veery, Myrtle [now Yellow-rumped] Warbler, Slate-colored [now Dark-eyed] Junco, White-throated Sparrow, Pink-eyed Vireo, and American Goldfinch.

“When totality comes,” Kellogg wrote, “one will get extra the impression of turning off a lightweight somewhat than that of the gradual and regular twilight… extra of a shock than we’re accustomed to expertise at nightfall.” Totality lasted for a couple of minute, though Kellogg famous that his eyes took lengthy sufficient to regulate to the darkness that it felt extra like 20 seconds in all.

“Because the darkness descended, chicken music fell off noticeably however some species, in keeping with our recordings, by no means did cease utterly.” he wrote. “The per-chic-o-ree of the Goldfinch was heard clearly in the course of the totality; the Hermit Thrush and Swainson’s Thrush sang weakly through the darkness; a Veery known as.” Regardless of the brief interval of darkness—about twice the brightness of a full moon, he wrote—no Jap Whip-poor-wills took the chance to sing. After the sunshine returned, the primary name was a spring peeper (frog), after which a White-throated Sparrow, a Hermit Thrush, and a Swainson’s Thrush.

Not understanding what to anticipate, Kellogg had opted for a directionless microphone somewhat than a parabolic. It allowed him to seize songs from throughout, however yielded poorer recordings than he might have gotten by pointing a parabolic mic at a singing chicken. “The outcomes of our recordings are considerably disappointing if seen solely from an leisure perspective,” he wrote. “Maybe probably the most worthwhile outcomes of our transient expedition had been some concepts as to methods to conduct such a examine sooner or later.” Amongst his suggestions:

- choose an space “recognized for its quietness and abundance of chicken life and music”

- watch, pay attention, and document within the space for no less than every week earlier than the eclipse

- use a lightweight meter and examine sounds heard through the eclipse with singing below comparable mild ranges at daybreak and nightfall on the day earlier than and day after the eclipse

“Such a examine, requiring each time and care, would presumably must be accomplished by fanatics somewhat than by paid observers,” Kellogg famous, in a nod to the sphere that might emerge over the following 50 years and develop into often called citizen science or participatory science. Kellogg himself compiled a number of experiences from birdwatchers elsewhere in New England: calling Widespread Nighthawks, White-throated Sparrows, and Swainson’s Thrushes close to Mt. Katahdin; and a bunch of gulls close to Marblehead Neck, Massachusetts, that took off for his or her roosting websites, solely to show round as quickly as the sunshine started to fill again in.

Within the eclipse that crossed North America in August 2017, scientists noticed bursts of surprising habits through the totality. Discover a number of the attention-grabbing questions that ornithologists are asking this time round, reminiscent of how the sudden darkness may have an effect on spring migrants. And add your personal observations to eBird utilizing these strategies.