From the Autumn 2023 situation of Dwelling Hen journal. Subscribe now.

This story initially appeared in bioGraphic, the journal of the California Academy of Sciences. It’s reprinted right here with permission.

The Japanese Black Rail is a subspecies of chicken that’s one of the crucial elusive creatures a wildlife biologist can select to review. Adults are the dimensions of a human fist. Chicks are the dimensions of golf balls. Each are darkish and shy, the higher to cover among the many dense marsh grasses underneath which they skulk and scurry. The birds are maddeningly troublesome to put eyes on. Search YouTube, which has hours of video of just about every little thing, and also you’ll discover simply eight movies of Japanese Black Rails, the longest of which is barely over a minute.

Hardcore birders strive in useless to examine this subspecies (Laterallus jamaicensis jamaicensis) off their life lists; those that do often hear the chicken reasonably than see it. Professionals do little higher: Christy Hand, a biologist with the state of South Carolina who’s been learning the Japanese Black Rail for almost 10 years, has seen solely a handful, every for only a few seconds.

For the previous decade, she’s pursued these minute birds all through her research space within the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto basin (also referred to as the ACE, named after the three rivers that meet there). It’s one of many largest undeveloped estuaries alongside the U.S. Atlantic coast. She remains to be not sure precisely what number of Japanese Black Rails stay there—just a few rating? just a few hundred?—however they’ve inhabited her thoughts.

“Individuals working with rails,” she says, “we are usually a bit quirky. I dream in regards to the rails. I don’t dream about Wooden Storks a lot as a result of I can simply have a look at them. However with the rails, I’m all the time receiveddering what’s occurring. I get these little glimpses and I feel my mind’s attempting to fill within the gaps.” In her thoughts she hears their distinctive kickee-doo tune.

The decision is a superb boon to Hand’s work, because it’s the simplest solution to find the birds. But taking a census of rails by sound is problematic, as a result of the birds don’t appear to have something like a set schedule of when they’re most vocal. Day, evening, daybreak, nightfall? They appear to favor no hour. This makes it difficult to design a standard point-count research, by which educated birders detect chicken presence by going out to look and pay attention for brief intervals at a exact time of day in a selected location. As well as, the rails typically transfer from place to put as water ranges of their marsh habitat change, so you may simply miss them even in a spot you understand a household of rails frequents.

To get a deal with on these birds, Hand has needed to strive new methods to seek out them and learn the way they stay. For some time, she would go into their habitat and play an audio recording of a Black Rail, then pay attention for replies. She’d get some. However she wished for one thing higher and fewer intrusive, partly out of concern that the synthetic calls would possibly disrupt the birds’ regular social behaviors.

About 5 years in the past, the falling costs of autonomous recording items, or ARUs, made it sensible to depart audio recording units within the subject to seize all of the racket close to a given spot. Then the issue turned the way to undergo all that audio. Listening to it in actual time would require a whole bunch of hours of painstaking work by individuals expert at figuring out birds by their vocalizations— probably not an possibility for a small group in a modestly funded state operation. Then in late 2020, Hand heard of a brand new bird-call recognition app referred to as HenNET, created by a younger programmer named Stefan Kahl of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The app creates a so-called deep neural internet—a synthetic intelligence algorithm that mimics the human mind’s decision-making routines. It excels at discerning, in advanced sonograms like these from Hand’s recordings, the distinctive shapes of particular person species’ songs, calls, grunts, buzzes, croaks, barks, and hisses. It streamlined into one course of the a number of steps of Hand’s previous toolset and will analyze a whole bunch of hours of sound in only a few days.

BirdNET turned out to be simply the quick and straightforward bird-ID instrument Hand was in search of. With Kahl’s assist, she has used her present audio recordings of Japanese Black Rails to coach the app to acknowledge these songs, and she will be able to now measure Black Rail presence in a quick, environment friendly, and low-impact method.

This previous spring she acquired 16 ARUs that her group organized throughout six wetland areas within the ACE basin, the place habitat administration for rails was already ongoing or deliberate. The battery-powered items, every the dimensions of a small paperback guide, file a number of hours a day within the morning and night. The sound goes onto SD playing cards that Hand pulls as soon as per thirty days to reap the info, which is backed up after which despatched to Kahl at BirdNET for processing. And for the primary time, Hand is collecting sufficient information from sufficient factors that she’s getting a greater really feel for the rail’s distribution. The information remains to be not broad sufficient to allow her to estimate the inhabitants. But it surely’s wealthy sufficient to assist her consider the consequences of the division’s administration instruments, akin to adjusting water ranges in impoundments and strategically burning vegetation to create rail-friendly floor cowl. The information will solely develop into richer as she collects it in subsequent years.

Through the calls and songs of adults and the twittering of juveniles, in addition to sure intervals of quiet (for the birds name far much less typically when sitting on eggs), Hand can be hoping to realize the power to detect the place and when the rails are breeding and elevating younger, in addition to whether or not the younger reside lengthy sufficient to fledge. On this method she’d be getting an unprecedentedly detailed have a look at the birds’ life histories and the way they use the totally different environments throughout the ACE basin. It’s nonetheless early instances. However the ARUs and BirdNET are opening new vistas for her. “It’s a complete recreation changer,” she says.

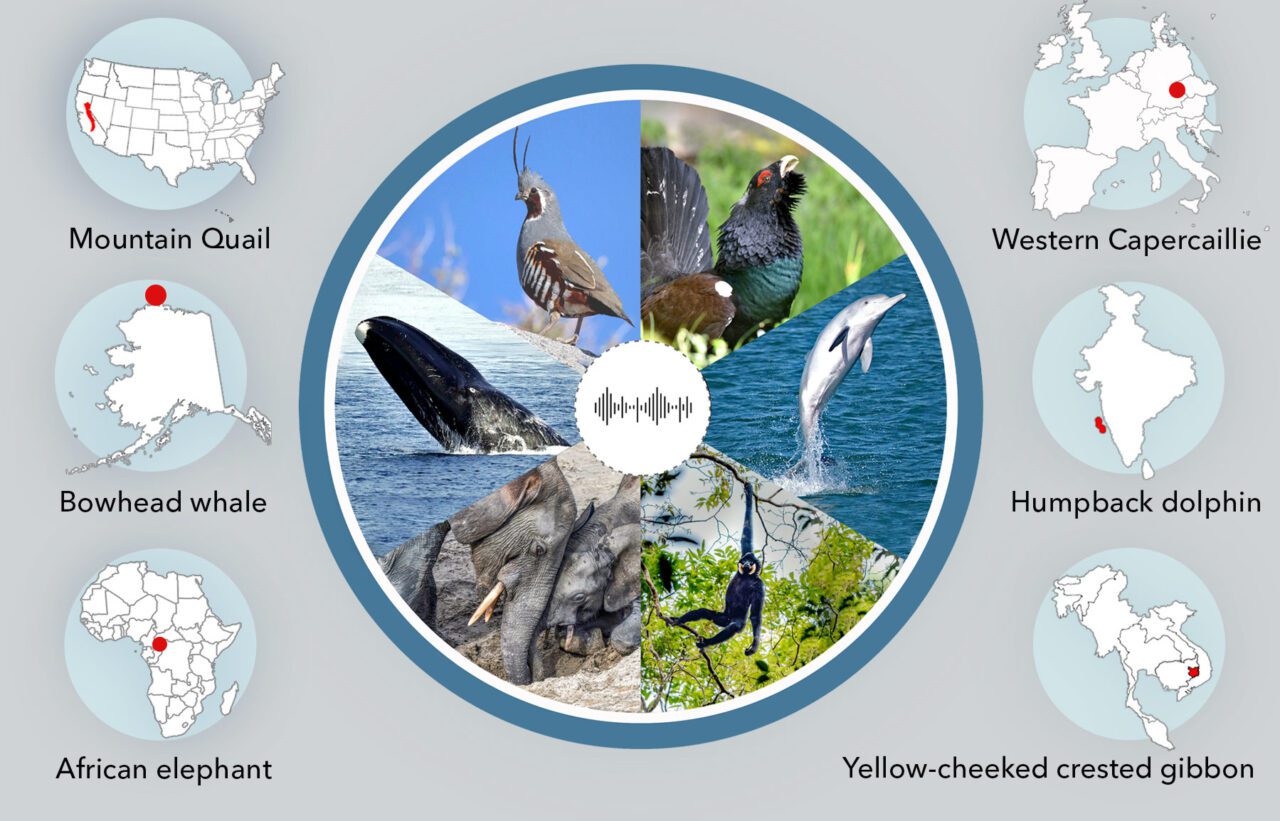

Listening to the Pure World: Land, Air and Sea

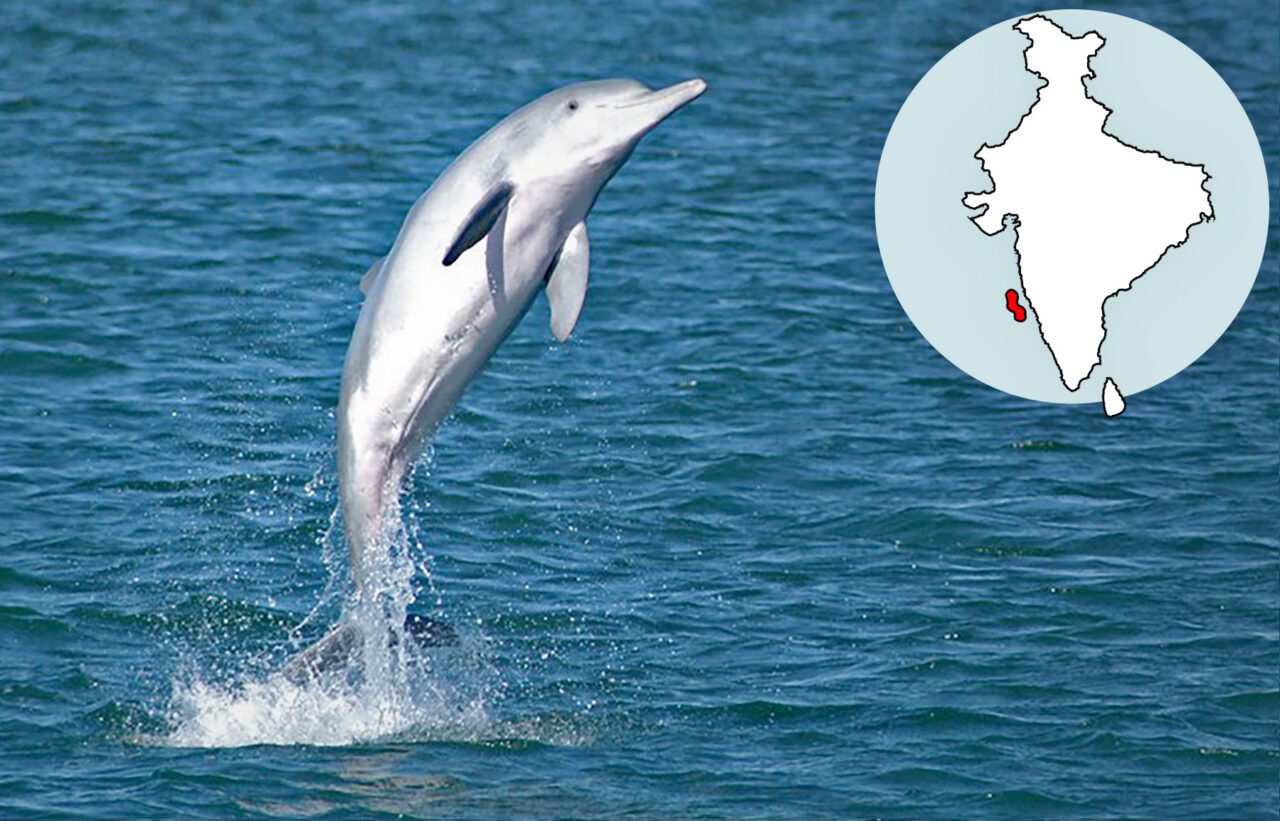

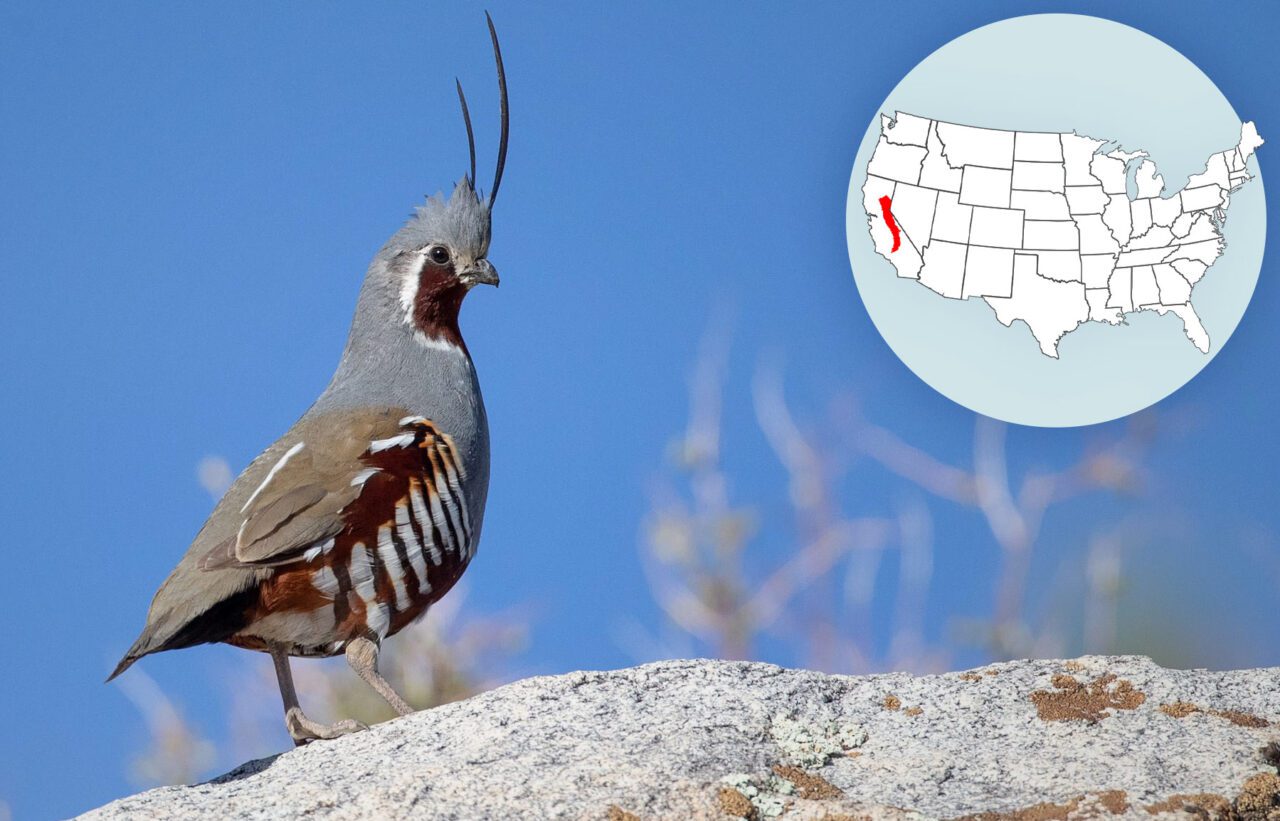

Within the Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary in Cambodia, an array of fifty Swift items has been deployed to evaluate the inhabitants standing of endangered southern yellow-cheeked crested gibbons in addition to hornbills and different birds. Photograph courtesy of Filip Agoo.

Hand is a pioneer of types, however she’s hardly the one researcher or conservationist to deploy ARUs and name recognizers. Over the previous few years, these newly environment friendly, transformative instruments have begun to revolutionize analysis and conservation observe across the globe, due to the velocity at which they’ll collect and course of details about animal and human presence.

The primary identified recording of any chicken occurred in 1889, when 8-year-old Ludwig Koch, the “godfather of chicken recording,” used an Edison cylinder machine to file the tune of a captive White-rumped Shama on the Frankfurt Zoo. The primary identified tutorial sharing of a recording got here 9 years later, when Sylvester Judd performed recorded songs of captive birds for the Congress of the American Ornithologists’ Union in Washington, D.C. And the primary identified recordings of untamed birds have been made in England, in 1900, when Cherry Kearton captured the songs of the Frequent Nightingale and Music Thrush.

Many observers, nonetheless, hint the beginning of bioacoustics as a scientific discipline to the work of William Schevill, a researcher at Harvard Faculty and Woods Gap Oceanographic Establishment, who first heard whale songs whereas eavesdropping on naval ships for the U.S. Navy in World Warfare II and shortly started recording them. In his 1949 paper “Underwater listening to the white porpoise,” one of many first scientific publications to concentrate on animal sounds, he described porpoise utterances that evoked an orchestra tuning up: “mewing and occasional chirps,” bell-like peals, feels like these of an echo sounder, and infrequently, “calls [that] would recommend a crowd of kids shouting within the distance.”

The many years since have seen thousands of bioacoustic research, most dedicated to sea mammals or birds. However prior to now half-dozen years or so, the event of low-cost, powerful audio recording items and quick, refined name recognizers is taking the sector of bioacoustics into new and thrilling terrain, each figuratively and actually.

This conservation bioacoustic work ranges from the carefully centered, like Hand’s rails, to the expansive. Analysis groups are utilizing recorders to review the dynamics of aggressive loon calls (who knew?); monitor delivery lanes for whales so vessels can reroute round them; observe how fish and coral larvae find their house reef by perceiving its distinctive sound; detect the presence of crop-devastating bugs earlier than they proliferate; and monitor protected lands for the sounds of unlawful logging and searching. They will even carry out a type of quickie well being examination on some ecosystems. In a easy however highly effective discovery, researchers conducting a research for The Nature Conservancy in Indonesia discovered that they might estimate the range of species in a Bornean forest simply by analyzing how a lot of the sound-frequency spectrum was occupied by animal vocalizations.

The granularity of any such information—its density in each area and time—is the important thing to its new energy. The flexibility to maintain tabs on species’ presence in lots of locations always, reasonably than sometimes, primarily creates a large new instrument exquisitely delicate to vary at each inhabitants and ecosystem ranges. It’s as if a big assortment of lenses have been merged into one big lens that would see issues the smaller ones couldn’t.

At some point this previous June, I took a stroll with U.S. Nationwide Park Service ecologist Aaron Weed round his office within the steeply hilled, sweetly forested 600 acres of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller Nationwide Historic Park in Woodstock, Vermont. This park’s woodlands, managed sustainably for properly over a century, are a part of a virtually contiguous forest stretching throughout some 30 million acres in northern New England and New York State—an space identified right here because the Northern Forest. Within the 1800s, settlers and sheep farmers lower this large forest exhausting, so {that a} panorama as soon as round 85% forested turned 80% cleared. Since then, partly by care and partly by benign neglect (because the farmers moved west to raised farmland), the woods have rebounded. They now cowl some 90% of the terrain.

This forest, nonetheless, in the present day faces a century by which a special human-made drive, local weather change, will alter its species composition and well being in broad, basic, and generally troubling methods. Weed is a part of a group making a regional system of bioacoustic observations to trace—and assist predict and handle for—these coming modifications. This enterprise, the Northeast Temperate Stock and Monitoring Community, coordinates research and information for 13 Nationwide Park Service holdings within the Northeast, from Acadia within the far north to a small holding in Morristown, New Jersey.

A major focus of this work is monitoring chicken presence inside these boundaries, as one of many “very important indicators”—together with elements akin to water high quality, forest cowl, and forest composition—of ecosystem well being. Marsh-Billings hosts greater than 125 chicken species, from Bobohyperlinks to waterthrush, over the course of a 12 months. For years, essentially the most rigorous tallies of those populations have come from volunteers who do spring level counts, going at daybreak to particular areas and writing down each chicken species they acknowledge by sight or sound in 10 minutes. To accompany a birder on such an outing, stumbling over rocks and roots or bushwhacking by dense brush to pay attention quietly as black flies mob you, is to understand each the volunteers’ devotion and what a labor-intensive course of it’s to assemble the data. But these level counts yield solely a single day’s price of information annually, and their accuracy varies with the experience of the volunteers.

In distinction, the ARUs Weed deploys can tally chicken presence from each day, offering a much more dynamic image of species presence. (They will also be mixed with point-count information to present extra correct outcomes than both methodology alone.) These ARUs, referred to as Swifts, are just like these utilized by Christy Hand: Every is a field of electronics that data each sound inside earshot at no matter intervals Weed specifies, day after day, so long as the temperature is between -31 Fahrenheit and 122 above.

On our stroll, Weed led me up a delicate slope forested with maple, birch, and ash to indicate me one of many items. The gadget was strapped at chest top to a maple, a white metallic field about 5 inches sq. and two inches deep. Eradicating the quilt uncovered three D-cell batteries, a circuit board, and a 128-GB SD card; from its backside caught a stubby microphone with a black foam windshield. Every single day for a number of weeks in spring, it activates from 5 to 10 a.m. and seven to eight.30 p.m. to file the morning and night chicken tune.

BirdNET within the subject

Researchers in Vermont are refining a custom-made model of BirdNET software program so it will probably distinguish between very related chicken songs, akin to vocalizations by Crimson-eyed and Blue-headed Vireos. The scientists are learning how totally different species use totally different forest habitats.

By listening in on birds’ each day actions in a number of areas—not simply round this park however the others within the 13-site monitoring community—Weed and his collaborators will collect a richer learn on how birds use particular kinds of woodlands. They are going to see, for example, how populations develop, shrink, or shift location because the emerald ash borer, a risk already, continues to decimate ash stands. They are going to be taught virtually instantaneously how varied chicken species and chicken communities reply to forest-harvesting regimes starting from selective harvesting to clear-cuts small and huge.

Proper now, nonetheless within the early levels, Weed and his colleagues are working to refine their very own localized variations of BirdNET. This includes checking BirdNET’s IDs one by one in opposition to skilled IDs of particular person songs to make sure that the algorithm will reliably make the hardest identifications—discerning, for instance, the refined variations between Crimson-eyed versus Blue-headed Vireo songs. They hope so as to add stereoscopic microphones that may inform when two related chicken songs come concurrently from totally different instructions, which might enable them to estimate the variety of people singing—to measure not simply occupancy, but in addition abundance. They usually hope so as to add bats, maybe frogs, and a few bugs to the species identified, for these, too, may be devilishly exhausting to tally.

The detailed granularity of ARU-acquired information will enable Weed and his colleagues to analyze one thing they’ve not but been capable of analyze: how the vocalizations of some chicken species affect the behaviors of others. In a lot of the Northern Forest, for example, vireos and Ovenbirds, which sing typically and loudly, take up plenty of the soundscape. “So how do different species reply to this?” asks Weed. “How do they adapt? Have they primarily been capable of create some area of interest area by having totally different frequencies?” As Weed places it, “There’s all types of cool stuff you may pull out of this information.”

Maybe most essential: As an altered local weather imposes a basic transformation of those forests—potentially changing Vermont’s iconic sugar maples with oaks, for example—Weed and his colleagues ought to be capable to extra readily see, and listen to, birds and different species adapt (or fail to adapt) to the altering panorama.

Maybe the busiest person of those bioacoustic instruments and methods is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s personal Ok. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, a 36-year-old division that has lengthy helped lead the sector. The middle in the present day is quickly increasing due to a $24 million endowment from philanthropist Lisa Yang in 2021. Loads of bioacoustics conservation tasks have been and are being achieved with out Cornell’s containment. However its expertise, funding, and gear growth have made the middle one of many largest gamers within the subject.

And its largest challenge to date stands out as a main demonstration of the self-discipline’s rising energy and potential. This challenge started in 2017 excessive in California’s Sierra Nevada with a easy query: Was the Barred Owl, an invasive species, a significant component within the ongoing decline of the native California Noticed Owl? The challenge would assist reply that query decisively—and likewise lay the groundwork for a much wider investigation within the area.

The query of whether or not Barred Owls threatened Noticed Owls usually was not a brand new one. Earlier within the 2010s, groups in each the Cascades of Oregon and the coastal mountains of northern California had proven that Barred Owls—which have been initially restricted to jap North America till altering land use and different elements allowed them to broaden westward starting within the 1800s—have been bullying and driving out Northern Noticed Owls, a subspecies already well-known for shedding old-growth habitat to logging. One group of researchers, led by the late Lowell Diller, who was a biologist with the Inexperienced Diamond Useful resource Firm, had proven in 2016 that when you eliminated Barred Owls from the disputed space (by taking pictures them), Noticed Owls would quickly reoccupy that space and resume profitable breeding. However that first experiment, the paper concluded, wanted to be confirmed by further research; if that occurred, the authors predicted, “this could possibly be the inspiration for growth of a long-term conservation technique for Northern Noticed Owls.” (See Proof of Absence, Dwelling Hen Spring 2016.)

Within the northern Sierra Nevada, in the meantime, the California Noticed Owl (a separate subspecies) additionally seemed to be threatened by an increasing Barred Owl inhabitants. Censuses stored there by federal, state, and college biologists confirmed the California Noticed Owl inhabitants (lengthy thought of by the state of California to be “of particular concern”) steadily declining. In the meantime, the Barred Owl intrusion continued southward. Many biologists nervous that the California Noticed Owl would quickly observe its northern cousin into federal threatened standing. And since Barred Owl intrusions can occur rapidly, time was of the essence.

One of many biologists researching this situation was Zach Peery, ecology professor on the College of Wisconsin–Madison. Peery had been monitoring the Noticed Owl’s decline since 2001, and he knew {that a} group in Washington state had been experimenting with ARUs to assist determine Northern Noticed Owls and Barred Owls there. Peery and Connor Wooden, one in all his PhD college students on the time, aimed to do one thing related within the Sierra Nevada, however on a a lot bigger scale. Their aim was to gather “motionin a position information” from the vast majority of vital Noticed Owl habitat in California—about 2,300 sq. miles, almost twice the world of Rhode Island—a feat that may have been unthinkable earlier than 2016.

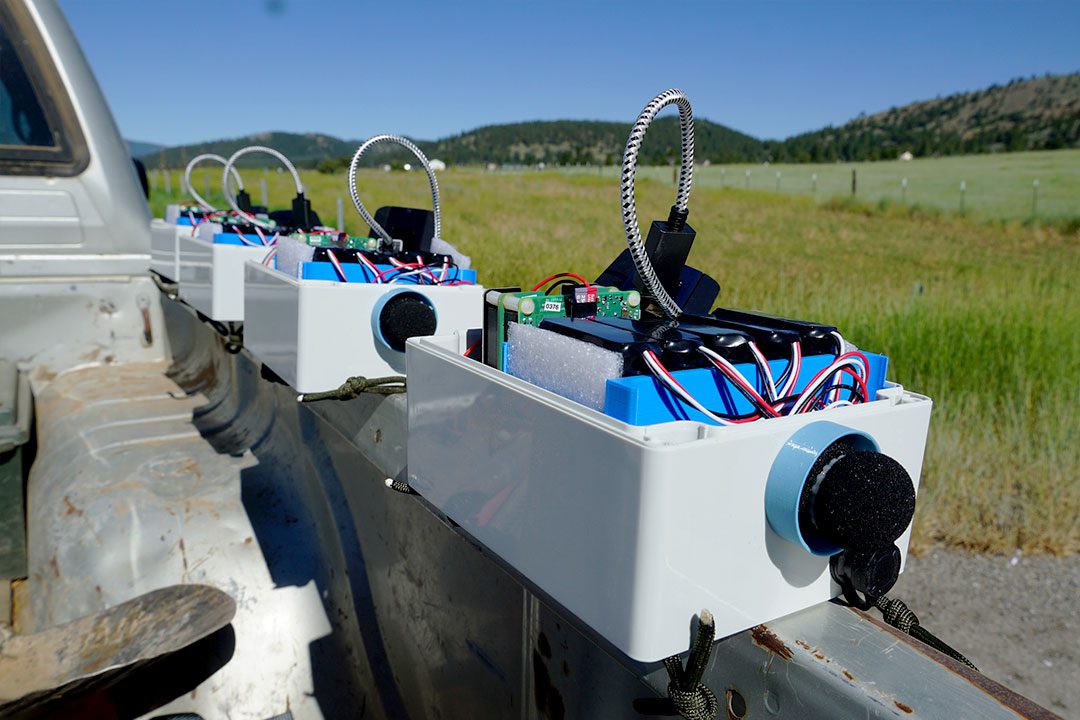

Having heard from the Washington group in regards to the Middle for Conservation Bioacoustics, Peery and Wooden contacted director Holger Klinck to see what he would advocate. Klinck mentioned he may need simply the factor: The middle had just lately began making mildweight, easy-to-deploy, comparatively inexpensive autonomous audio recorders (which might quickly be branded as Swift recorders) that could possibly be left within the subject for weeks. Maybe extra essential in making the challenge viable, the middle had additionally created a software program package deal, referred to as Raven, that could possibly be calibrated to acknowledge particular chicken songs and calls amidst the forest soundscape.

Having reviewed information on typical Noticed and Barred Owl densities, the sizes of their territories, and out there habitat, in addition to challenge funds, the researchers concluded that getting a consultant sampling of the birds’ distributions would require some 100 items rotated by 167 websites. The plan was to have Wooden and 5 subject technicians take the Swifts, strap them to bushes scattered in a randomized sample across the Noticed Owl’s vital habitat over two consecutive summers, and see if the Barred Owl was certainly taking up the Noticed Owl’s terrain.

Regardless of the early state of the technology, Klinck felt assured it might work. His solely actual concern, which he stored largely to himself, was logistics—whether or not, in brief, the group might deploy and handle so many ARUs directly. To not point out the truth that the 28-year-old Wooden had by no means labored with audio gear or audio-processing comfortableware, managed a big subject crew, or, for that matter, studied owls.

What Wooden and his group lacked in expertise, they made up for with power and willpower. For weeks, up a number of thousand toes within the Lassen and Plumas Nationwide Forests in northern California, they arrange the Swifts; deployed them; visited them every week later to change out their batteries, take away their SD playing cards, and swap in contemporary ones; then moved them to new websites. By the top of the primary summer season, the group returned to Wisconsin having collected some 49,000 hours of forest noise, which Wooden then ran by an audio processing instrument he developed with the Raven software program.

Lastly, after manually reviewing all obvious detections, Wooden and his group have been capable of produce a exact map of each “occupancy,” or sonic seemance, of a Noticed or Barred Owl. The map confirmed that inside this huge research space, which included a lot of the California Noticed Owl’s vital habitat, Barred Owls had encroached upon Spotted Owls in about 8% of viable forest.

The following 12 months, 2018, the analysis group expanded its operation with extra surveys and gear. They surveyed each web site thrice to acquire extra information, returning that fall with an additional 145,000 hours of audio. That produced one other map of the owls’ territories that Wooden and his group might examine to the one from the earlier 12 months. The image was not fairly: The second map confirmed that the Barred Owl had expanded its share of the Noticed Owl’s most well-liked habitat to 21%.

The Barred Owl, in different phrases, instantly occupied a fifth of the California Noticed Owl’s finest habitat and was possible spreading. The information, Wooden would inform me later, couldn’t have been clearer. The Barred Owl was taking up. And it was going to wipe the Noticed Owl off the map.

That winter, in February 2019, when Wooden offered the group’s findings to the annual assembly of the Western Section of the Wildlife Society—a bunch that had been monitoring and debating the owls’ fates for greater than twenty years—the conclusion was fast: Eachone now agreed that the Barred Owls within the research space needed to go.

Inside weeks, the U.S. Forest Service and personal timber firm landowners agreed on a Barred Owl culling campaign, which was executed that spring each on federal and personal land. A 12 months later, Barred Owls inhabited simply 3% of the disputed habitat, and the California Noticed Owl had recolonized 56% of its former vary.

A 2022 analysis evaluation of the culling marketing campaign’s outcomes printed within the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Setting concluded that the professionalgram had “averted the in any other case possible extirpation of California Noticed Owls” in that area (see Acoustic Monitoring Exhibits Want for California Noticed Owl Protections, Dwelling Hen, Summer time 2022).

That’s not essentially the top of the Noticed Owl story, after all. Research have proven that Barred Owls someinstances return to areas the place they’ve beforehand been eliminated, and most consultants agree that the species is within the Pacific Northwest to remain, making repeated removals obligatory. Some biologists fear that Barred Owls are in order that aggressive that such measures will fail in the long term.

Within the meantime, although, the two-year Frontiers research demonstrated that the brand new bioacoustic instruments can collect actionable information at a big scale in a brief time period, and seize real-time dynamic occasions just like the displacement of 1 species by one other.

Within the summers since, the group has expanded its Sierra Nevada challenge. Wooden, who’s now a analysis affiliate on the Cornell Lab learning biodiversity conservation by bioacoustics and quantitative ecology, is working with collaborators and even bigger subject crews to put in Swifts throughout a good bigger space. The brand new grid is unfold throughout not simply the previous research space in northern California, however a lot of the Sierra Nevada vary—an space roughly 400 miles lengthy and from 50 to 80 miles throughout. They’ve deployed greater than 1,600 Swifts, 4 instances as many as within the unique challenge.

The group can be broadening the scope of its analysis: This time they may monitor greater than 100 chicken species, in addition to wolves and the Yosemite toad, which breeds solely within the spring snowmelt excessive within the Sierra. The challenge ought to allow them to trace not simply species of particular concern but in addition how varied animal populations and ecosystems reply to the impacts of local weather change—each gradual and sudden—in addition to efforts to handle habitats and mitigate these impacts by such measures as forest thinning and prescribed burns.

The rising ease and falling price of bioacoustic applied sciences are making a wildlife and ecosystem science that’s not simply sooner and extra highly effective, however extra inclusive. Several Yang Middle packages, for example, are offering coaching and gear for native communities at distant websites in Asia, Central America, Africa, and different biodiverse spots in order that researchers there can do work pushed by Indigenous pursuits and issues. These investigations vary from the welfare of key species to the enforcement of legal guidelines regulating logging, development, and searching.

In any respect of those areas, Yang Middle researchers at the moment are turning a few of their most distant tasks into studying facilities to present Indigenous analysis communities deep grounding within the operations and prospects of those instruments. The Yang Middle calls this “capacity constructing,” and it’s one of many three pillars of the middle’s mission, together with analysis and know-how development. For a very long time, says director Klinck, this capacity-building pillar was underfunded. The $24 million present from Yang in 2021 solved that downside.

“If we actually need to have a world impression,” says Klinck, “we can’t be the bottleneck. It’s not scalable if individuals can’t do it for themselves.” Klinck and his Yang Middle colleagues need to allow researchers of all origins and paths to pursue the numerous sorts of investigations the newer, extra highly effective bioacoustics instruments make potential. To this finish, Yang Middle biologists are creating yearlong coaching packages in the usage of ARUs, BirdNET, and different bioacoustic instruments, in addition to research design, in order that native collaborators are capable of each use these instruments themselves and train others to take action. The aim is to not simply develop collaborators however to mentor a brand new generation of impartial researchers.

In Africa, for example, the Yang Middle’s long-running Elephant Hearing Venture makes use of ARUs to listen in on elusive forest elephants and determine gunshots of poachers. It has helped practice an impartial group within the Republic of the Congo that’s operating essential features of a 50-site acoustic grid within the 1,514-square-mile Nouabalé-Ndoki Nationwide Park, which is linked to different protected areas. Working with the Wildlife Conservation Society, the Elephant Listening Venture can be establishing an evaluation and coaching hub in central Africa with solar energy methods and high-performance computers to course of the acoustic information, in addition to employees who can run the algorithms to detect elephants and gunshots. This hub will function a central processing and coaching heart for different subject groups operating bioacoustic tasks across the area, and can invite college students from the area to work on impartial analysis tasks there. Right here once more, the concept is to switch the Yang Middle because the hub, transferring evaluation capability into the palms and lands of native individuals. Yang Middle groups in Central America and Indonesia are launching related efforts, with funding in gear and long-term coaching packages.

This distributed capability highlights one of many nice powers of the brand new bioacoustic know-how, which is its fluid scalability. ARUs and name recognizers like BirdNET can work at something from a one-site operation all the best way as much as ecosystem and panorama scales and nonetheless be manageable each within the subject and within the lab, workplace, or, for that matter, an individual’s house. One of many merchandise of this revolution is a comparatively low-cost call-recognizing gadget referred to as Haikufield—an ARU offered for family use that gives identifications of the songs, chirps, and peeps of yard birds.

The gadget, powered by a family electrical outlet, mounts to any wall or tree and, utilizing a modified model of BirdNET, identifies birds inside earshot in actual time. Through a smartphone app or internet interface, customers can take heed to recordings from the previous 24 hours, get notified when particular birds are detected, and look at historic charts displaying when birds have visited. They will additionally share that information with researchers by having it uploaded to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. As a latest WIRED evaluation put it, it’s “one of many uncommon items of know-how that truly will increase your connection to the world round you, reasonably than chopping you off.”

Klinck, not surprisingly, has one in his personal backyard. This previous spring, whereas the info servers at his workplace dissected audio from everywhere in the globe, the app on his cellphone chirped with the most recent information from his yard Haikubox. The 12 months’s first Baltimore Oriole had proven up close to his house in Ithaca. By this one mellifluous measure, spring had arrived.

In regards to the Creator

David Dobbs is the writer of three books and scores of articles on science, tradition, medication, and pure historical past in publications akin to The New York Instances, WIRED, and The Atlantic. See extra of his writing on his web site.